The Usual: The Solace of Sol Food

Framed outside the front door of Puerto Rican restaurant Sol Food in San Rafael, is a complaint. Not a Yelp review, but a real-live letter, handwritten in cursive, from 2006: “Dear Mrs. Hernandez, The lime green color you selected for your new restaurant is garish and ugly. That color may be appropriate for Puerto Rico, but it isn’t for Marin County.”

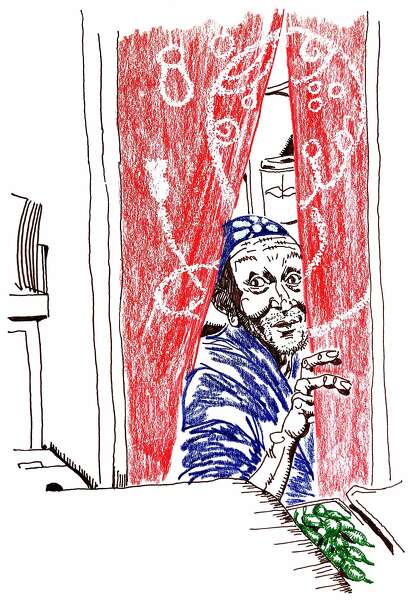

It makes Christopher Adam Williams laugh, like a lot of things do. “People who don’t understand culture will complain about color,” says the Sol Food regular. “When I saw the green, I was, like, OK, this food has personality. You expect a colorful restaurant to be good!” He admits his theory isn’t foolproof. (“I’ve been hoodwinked before.”) Still, as someone who paints canvases that measure nearly 7 by 6 feet and celebrate Black joy in purples and pinks, “bright, bold color calls me in,” he says. “It’s a sign of hope.”

As was his first date with Nakeyshia Kendall, in 2018. “It wasn’t a date,” Nakeyshia says, rolling her eyes. “I was just hungry.”

An educator-entrepreneur, she was looking for an artist to lead a group of middle-schoolers in painting a mural. He was a recent graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute. They met up at the annual Art Market in Fort Mason, where he proposed coffee at Starbucks. She suggested a drive across the bridge to Sol Food instead. The wait for a table was the same as it always was: long. So, they got takeout, drove up to the Marin Headlands, and talked art and music and relationship status (single), as they watched the sun dip into the bay. “We had slow jams going in the car,” Christopher adds. (Date.)

Nakeyshia learned about Sol Food the way most outdoorsy, food-loving locals do — googling for somewhere to eat after biking or hiking in Marin. In a county with a restaurant scene about as diverse as its population (affluent, 85 percent white), Sol Food stood out back when Marisol Hernandez opened the restaurant in 2004. It still does. She expanded to a larger location, then opened a second, in Mill Valley, in 2013. People come from all over the Bay Area — and everywhere from India to Italy — for her tender bistec encebollado and pescado frito Friday special, and garlicky, oregano-spiked pollo al horno (three pieces for Christopher, two for Nakeyshia). As Hector Lugo, a longtime Oakland regular, puts it: “Marisol’s menu is honest. She doesn’t try to do fancy things like all the Nuevo Latino cuisine bulls— I can’t stand,” he says. “Who are these chefs who think they can improve upon generations of delicious dishes?”

Even Nakeyshia’s Guyana-raised mother — who considers all “restaurant food junk food” — is a fan. “It reminds her of her own cooking,” says Nakeyshia. Though she grew up in Florida eating plantains and rice, it’s not so much Sol Food’s food that reminds Nakeyshia of home as its soul. The way it feels. The people she shares it with.

Christopher, who’d been living off mostly fast-food as a student, fell hard for Nakeyshia and her favorite restaurant. “It was real food,” he says recalling the Cubano. A month after that first meal together, Christopher and Nakeyshia took off on a cross-country road trip to Maine, to drop Christopher at graduate school. Their last stop before leaving town: Sol Food. “Everything was downhill from there,” he says.

It started with really bad barbecue in Idaho. (“All of a sudden he turned serious and went on this tirade against the baked beans!” recalls Nakeyshia. “I had no idea he was this barbecue connoisseur.”) The other thing about Idaho: There were very few Black people. “We tallied how many we saw in each state,” says Nakeyshia. Three in Idaho. Zero in South Dakota, where they were served “pasty mashed potatoes out of a can” and some dude asked Christopher if he was on the Oakland A’s. (For the hell of it, Christopher said he was and signed his autograph.) They ate passable macaroni and cheese in Wisconsin, and a “world-famous meatball” in upstate New York, but they missed Sol Food. And more.

In Maine, Christopher faced racist cops and hate-emails, as well as stares every time he walked into a restaurant. “I was literally the only Black guy around. I felt like I was on display,” he says. The lobster rolls were decent, but not the people serving them. He remembers once ordering two — “and the lady goes, ‘That’s going to cost $40, you know.’ I was, like: ‘Yeah, I know.’” It might’ve been summer in Maine, but the state felt cold. Within six months, he drove West. First stop in California: Sol Food. “I was back where I belonged,” Christopher says.

He was also back with Nakeyshia. Eleven months later, they got married at Fort Mason. (Wedding catered by Sol Food, naturally.) Before COVID-19, Bianca, a server in Mill Valley, would find them a table, and gift them flan. Salt ‘n Straw always gives them free ice cream, too. “We don’t know why!” Nakeyshia says with a laugh. “I think they just like our vibe. You don’t see a lot of Black couples in San Francisco.”

As a Black couple walking around San Francisco, they’re also often asked: “Are you lost?” And then there’s the time Christopher was accused of breaking into his own car. As a Black man, he encounters more racism when he’s not with Nakeyshia, he says. It’s been better during quarantine, she says, “Because we’re always together.”

As they are on this summer day, chatting in camping chairs with purple masks around their necks and to-go containers in their laps. It’s easy to see, from 6 feet away, why Christopher and Nakeyshia get free flan. The virus is surging, unemployment is rising, systemic racism remains, and yet: This couple’s contentment with lunch and life and each other is contagious, in a good way. Early in the lockdown, Christopher and Nakeyshia rarely left their Russian Hill neighborhood. They shopped locally, took 6 a.m. walks, watched Trevor Noah. Until one day in May, they decided to take a road trip of a different sort.

They donned their matching masks and cruised over a Golden Gate Bridge devoid of traffic. “It felt like such an adventure,” recalls Nakeyshia. The sun was beaming. The line wasn’t bad. Bianca waved. They collected their collective five pieces of baked chicken and pink beans and white rice and extra maduros and headed for the headlands. Damn COVID, it was closed. No matter. They ate their Sol Food somewhere else appropriate, shelter-in-place or not: home.